Parasailing accidents don’t happen randomly. When a towline snaps hundreds of feet in the air or a sudden wind gust drags a participant into a pier, specific factors caused that outcome. Understanding the most common causes of parasailing accidents helps injured participants and their families make sense of what went wrong—and whether operator negligence played a role.

Most parasailing accidents trace back to three categories: equipment failure, operator error, and hazardous weather conditions. These factors often overlap. A worn towline might hold under normal conditions but fail when an operator launches in excessive winds. This article breaks down each cause category, examines real incidents that illustrate these failures, and explains when parasailing operators may be legally responsible.

What Causes Most Parasailing Accidents?

Parasailing creates inherent risks. Participants are towed behind a boat at heights of 300 to 500 feet, suspended by equipment that must withstand significant stress. When accidents occur, they typically result from failures in one or more of three areas.

The role of equipment in catastrophic failures

Equipment failure is the leading cause of severe parasailing injuries and fatalities. The towline connecting the parasail to the boat bears enormous loads during flight. When it fails, the parasail becomes an uncontrolled kite, carrying participants into the water, land, or obstacles. Harnesses, winches, and attachment points can also fail catastrophically.

Why operator decisions matter

Operators make critical decisions about when to launch, how to maintain equipment, and how to respond to emergencies. Poor weather judgment—launching in conditions that exceed safe limits—is the leading operational error in parasailing accidents. Inadequate maintenance, improper emergency responses, and overloading also contribute.

Environmental factors that create danger

Wind speed is the most critical environmental factor. Industry standards establish clear limits, but operators sometimes ignore them to maximize revenue. Onshore winds create particular danger because a detached parasail will blow participants toward land, structures, and power lines rather than open water.

How Does Equipment Failure Cause Parasailing Accidents?

Call us today at (305) 694-2676 or

contact us online for a free case evaluation.

Hablamos español.

Equipment failure accounts for the majority of serious parasailing injuries and deaths. The equipment holding a participant aloft must perform flawlessly under stress. When any component fails at altitude, the results are often catastrophic.

Towline failures: The leading equipment cause

The towline is the single most critical failure point in parasailing operations. According to NTSB analysis, towline failure accounts for the majority of serious injuries and fatalities. These failures don’t happen suddenly—they result from cumulative degradation that operators often ignore.

Several factors cause towlines to weaken over time:

- Salt crystal accumulation. Repeated exposure to seawater causes salt to build up within the rope fibers, creating abrasion from the inside out during winching operations.

- UV exposure. Sunlight degrades synthetic rope materials, weakening load-bearing capacity even when the line appears intact externally.

- Cyclic compression. Each flight cycle subjects the towline to repeated stress during winching, gradually weakening the fibers over hundreds of flights.

- Knotting stress. NTSB testing found that bowline knots reduce rope strength by more than 20% and create stress concentration points where “necking” (thinning) occurs before failure.

- Exceeded service life. Operators often use towlines well past their safe service life because spectra and dyneema lines are expensive to replace. Without tracking flight cycles, degradation goes undetected.

- Undetected fraying. Internal fraying and corrosion may not be visible during casual inspections, allowing weakened lines to remain in service.

Harness and attachment point defects

Harnesses secure participants to the parasail canopy. These components endure constant exposure to saltwater and sun. Buckles and straps degrade from saltwater corrosion. UV damage weakens load-bearing webbing even when it looks intact. When harnesses fail under load, participants fall from height with nothing to slow their descent.

Attachment points—where the harness connects to the canopy and where the towline connects to the boat—also weaken from repeated stress cycles and corrosion. These failures may occur suddenly during normal operational loads if maintenance has been deferred.

Winch system malfunctions

Hydraulic winch systems control the towline during ascent and descent. These systems can fail in several ways. Hydraulic jams prevent retrieval during emergencies, leaving participants stranded as conditions deteriorate. Hydraulic leaks cause unpredictable behavior. Unexpected releases during operation can cause rapid, uncontrolled descent.

Poor maintenance of hydraulic components contributes to these failures. When operators defer winch maintenance to cut costs, the risk of catastrophic malfunction increases.

What Operator Errors Lead to Parasailing Accidents?

Equipment doesn’t maintain itself. Operators make daily decisions about maintenance, weather conditions, and safety procedures. When those decisions prioritize revenue over safety, accidents follow.

Weather judgment failures

Operating in high winds is the leading operational error in parasailing accidents. NTSB pattern analysis found recurring accidents in winds exceeding 20 mph. Operators face financial pressure to run trips even in marginal conditions—a canceled trip generates no revenue.

Common weather judgment failures include:

- Launching in winds exceeding safe limits. Industry standards (ASTM F3099) cap sustained winds at 20 mph and gusts at 25 mph, but some operators ignore these limits.

- Prioritizing revenue over safety. When conditions are borderline, operators may choose to launch rather than refund customers and lose income.

- Failing to monitor weather changes. Conditions can deteriorate rapidly during operations. Operators who don’t continuously monitor forecasts may be caught with participants aloft when dangerous weather arrives.

- Ignoring forecasts. Some operators launch without checking current conditions or forecasts, relying instead on visual assessment.

- Misjudging gust differentials. A gust differential greater than 15 mph between sustained wind and gusts creates critical risk, even if sustained winds are below the 20 mph threshold.

Maintenance and inspection neglect

Equipment degradation is predictable. Towlines weaken over flight cycles. Harnesses deteriorate from salt and sun exposure. Responsible operators track usage and replace components before failure. Negligent operators extend equipment life to save money.

Common maintenance failures include skipping daily inspections, failing to track flight cycles on towlines, using lines past their safe service life, and deferring winch system maintenance. These shortcuts save money in the short term but create conditions for catastrophic failure.

Emergency response breakdowns

When equipment fails or conditions deteriorate, proper emergency response can prevent injuries from becoming fatalities. Many parasailing accidents are worsened by inadequate emergency procedures.

Operators may be unable to execute “chute assist”—using a secondary boat to collapse the canopy and control descent when the towline fails. Improper vessel maneuvering after a line snap can drag victims through the water or into obstacles. Operations without a dedicated observer leave captains multitasking during emergencies, reducing response effectiveness.

How Do Weather Conditions Contribute to Parasailing Accidents?

Parasailing is fundamentally a wind-dependent activity. The same force that lifts participants creates danger when conditions exceed safe limits or change suddenly.

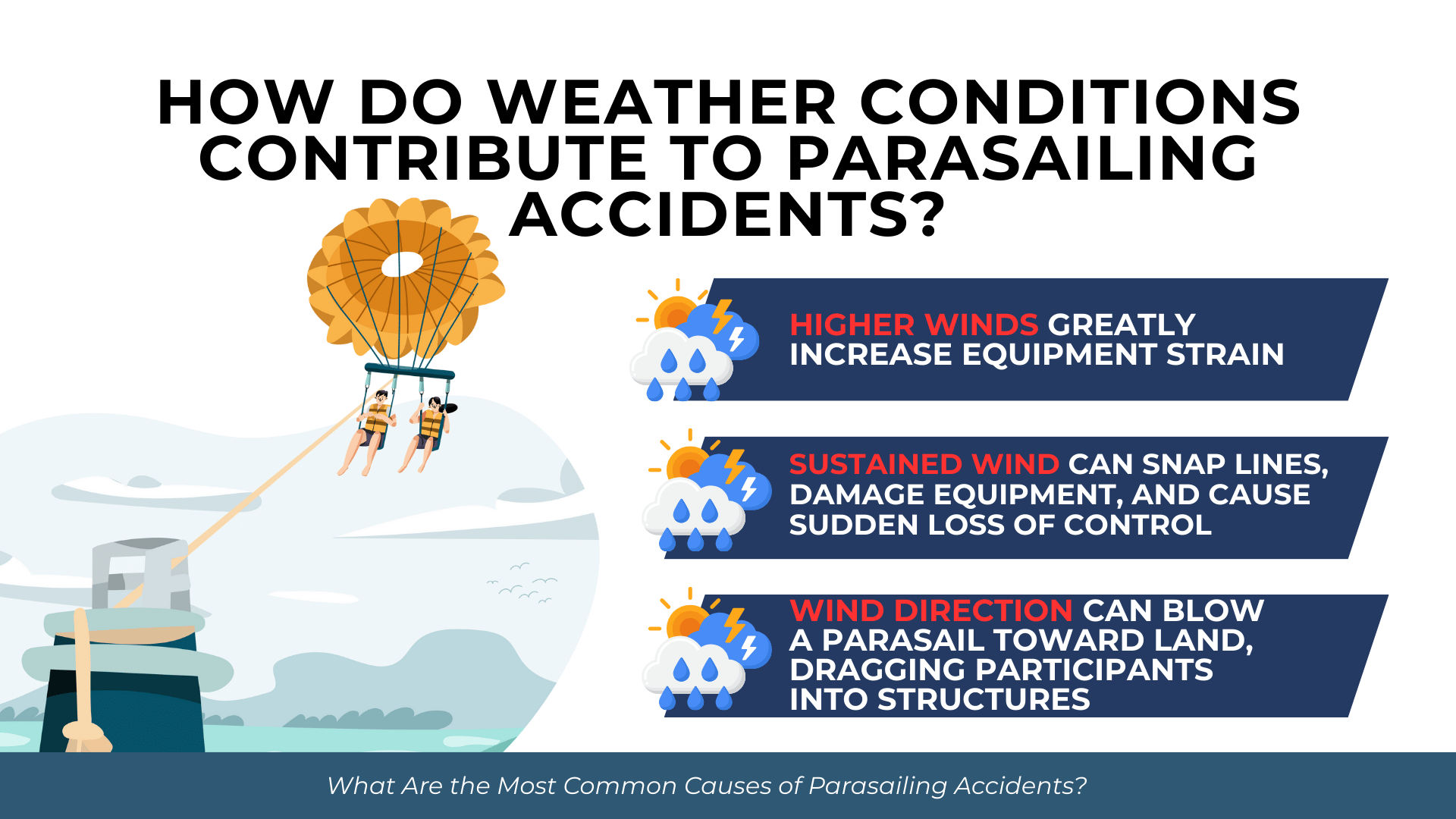

Wind speed limits and why they matter

Industry standards exist for good reason. ASTM F3099—the voluntary standard for commercial parasailing—establishes a maximum sustained wind speed of 20 mph with a gust cap of 25 mph. Florida’s White-Miskell Act codifies similar requirements into state law.

These limits aren’t arbitrary. Higher winds place greater stress on towlines, harnesses, and attachment points. Equipment that performs safely at 15 mph may fail at 25 mph. Wind speed also affects controllability—a detached parasail in high winds becomes an unpredictable projectile.

The danger of sudden gusts

Sustained wind speed tells only part of the story. The gust differential—the difference between sustained wind and peak gusts—creates particular danger. A critical risk threshold exists when this differential exceeds 15 mph.

Sudden gusts can snap towlines that would otherwise hold. They can tear harnesses or rip canopy attachment points. Even if equipment holds, gusts can cause rapid altitude changes and loss of control. Operators who monitor only sustained wind speed miss this critical factor.

Onshore winds and lee shore hazards

Wind direction matters as much as speed. Onshore winds—blowing from water toward land—create what maritime professionals call a “lee shore” hazard.

If a towline snaps during onshore wind conditions, the detached parasail doesn’t drift harmlessly over open water. Instead, wind blows the canopy and attached participant toward land. This has resulted in participants being dragged into buildings, piers, and power lines. The Ocean Isle Beach fatalities occurred in exactly this scenario—victims were dragged by an inflated canopy into a pier after the towline snapped.

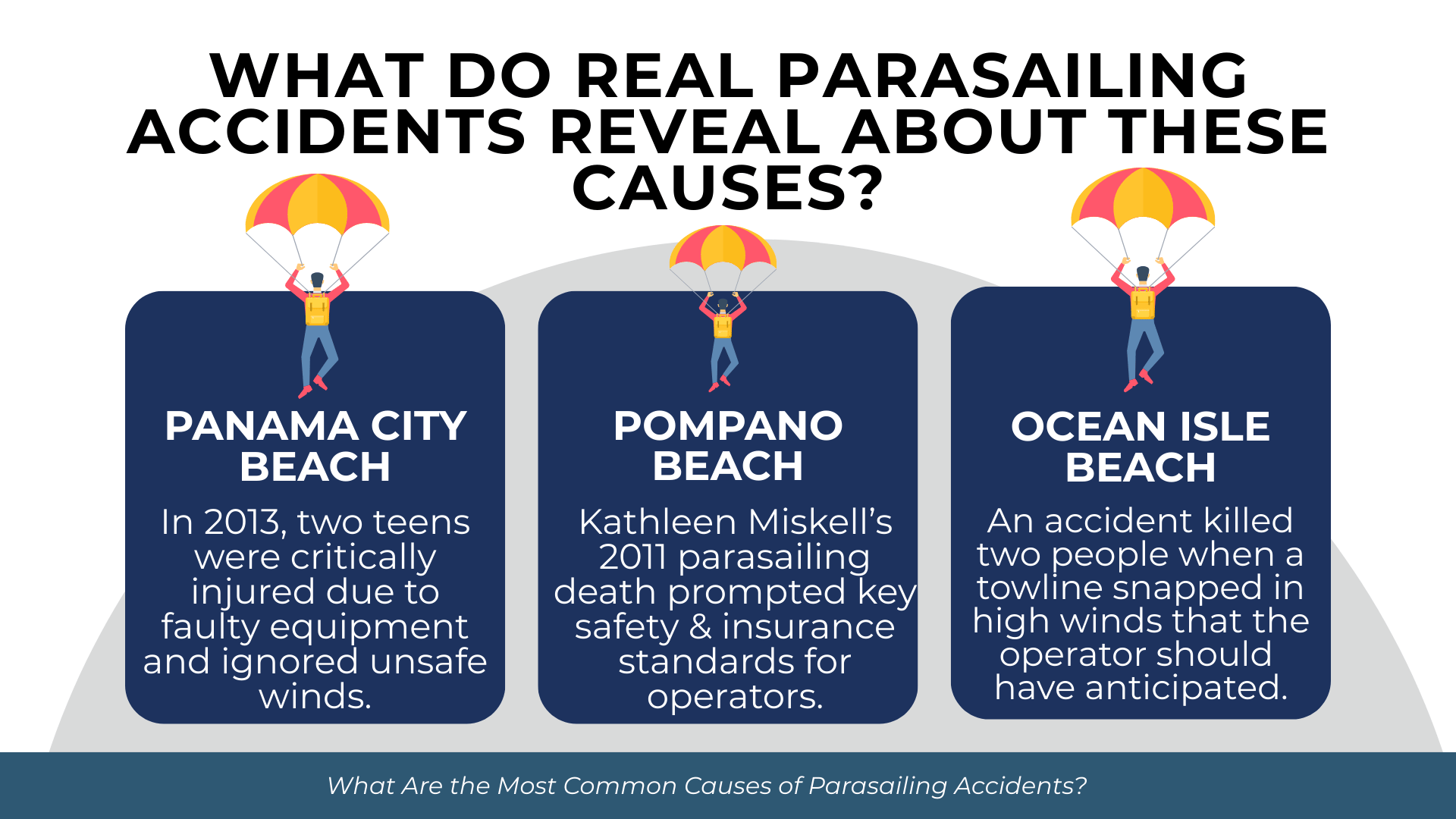

What Do Real Parasailing Accidents Reveal About These Causes?

Get started with your complimentary case evaluation today;

call us at (305) 694-2676 or reach us online using our

secure contact form.

Examining actual incidents illustrates how equipment failure, operator error, and weather combine to cause tragedy. These cases also reveal recurring patterns that the NTSB has documented across multiple investigations.

Panama City Beach: Equipment failure in high winds

In 2013, two teenagers were critically injured when their parasailing towline broke in high winds over Panama City Beach, Florida. The detached parasail collided with power lines and a building before crashing.

Investigation revealed faulty equipment combined with operator failure to heed weather warnings. The operator launched despite conditions that exceeded safe limits. Equipment that might have held in moderate conditions failed under the added stress of high winds.

Pompano Beach: The Kathleen Miskell tragedy

The 2011 Pompano Beach parasailing fatality became a catalyst for regulatory change in Florida. Kathleen Miskell died when her harness failed mid-flight. She plummeted approximately 200 feet into the ocean.

Coast Guard investigation highlighted poor maintenance as the cause. The harness had aged and weakened from UV exposure but remained in service. This incident led directly to Florida’s White-Miskell Act, which established insurance requirements, weather monitoring obligations, and operational standards for parasailing operators in the state.

Ocean Isle Beach: Towline failure and pier collision

An Ocean Isle Beach, North Carolina accident killed two victims when their towline snapped in high winds. The inflated canopy dragged both victims into a pier.

Investigation found the operator had not monitored weather forecasts predicting gusts exceeding safe limits. The accident demonstrated how weather conditions and equipment failure combine—the towline failed under stress created by winds the operator should have anticipated.

What NTSB pattern analysis shows

The National Transportation Safety Board has assisted in six parasailing cases involving equipment misuse. Their analysis reveals consistent patterns: towline failure accounts for the majority of serious injuries and fatalities, failures recur in winds exceeding 20 mph, and inadequate inspections are consistently cited as contributing factors.

These aren’t isolated incidents. They represent predictable outcomes when operators neglect maintenance, ignore weather conditions, or push equipment beyond safe limits.

When Is a Parasailing Operator Legally Responsible for an Accident?

Understanding what caused an accident is the first step. Determining whether the operator bears legal responsibility requires examining their duties under maritime law and state regulations.

The duty of reasonable care

Parasailing operators owe participants a duty of reasonable care under the circumstances. This is the foundational standard under general maritime law. Operators are not held to a heightened “common carrier” standard because parasailing is classified as a recreational service, not transportation.

However, reasonable care in the parasailing context includes specific obligations. Operators must inspect equipment for hazards before each trip. They must provide adequate instruction on safety procedures. They must warn of known hazards including weather conditions. These duties apply regardless of any waiver participants sign.

Florida’s White-Miskell Act requirements

Florida enacted specific parasailing regulations following the Kathleen Miskell fatality. The White-Miskell Act (Florida Statute § 327.375) establishes mandatory requirements that define the standard of care for Florida operators.

Key requirements include:

- Insurance coverage. Operators must maintain $1 million in bodily injury coverage per occurrence and $2 million in annual aggregate liability coverage. Proof must be available to customers.

- Weather monitoring equipment. Operators must have VHF radio and National Weather Service monitoring devices. They must log all weather conditions.

- Mandatory operational suspension. Operations must stop when winds exceed 20 mph sustained, when rain, fog, or other visibility impairment occurs, or when lightning is detected within 7 miles.

- Weather log maintenance. Operators must maintain detailed weather logs and provide access to investigators.

- Vessel standards. Parasailing vessels must meet Coast Guard standards for transporting passengers with proper safety equipment.

For civil cases, regulatory violations help establish that an operator failed to meet the applicable standard of care.

What operators must do to meet safety standards

Beyond statutory requirements, reasonable care requires operators to track equipment usage, replace components before failure, train staff on emergency procedures, and cease operations when conditions become dangerous. Operators who cut costs by extending towline life, skipping inspections, or launching in marginal weather breach their duty of care.

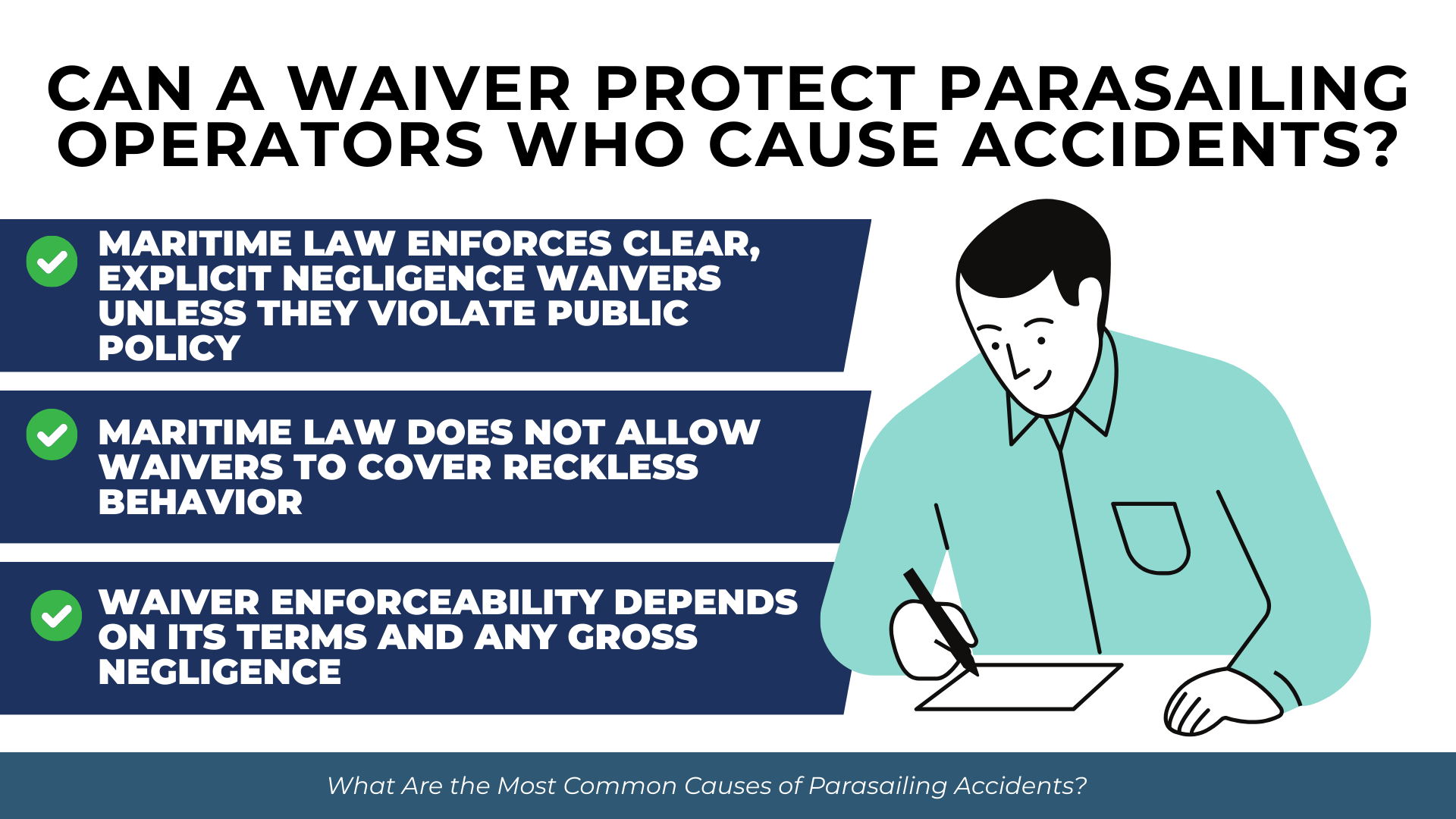

Can a Waiver Protect Parasailing Operators Who Cause Accidents?

Parasailing operators require participants to sign liability waivers before each trip. Many accident victims assume these waivers prevent any legal claim. That assumption is often wrong.

When waivers are enforceable

Maritime law governs liability waivers for recreational activities on navigable waters. Exculpatory clauses are generally enforceable if they are clear, unambiguous, and not contrary to public policy. A properly drafted waiver must clearly state that the participant releases the operator from liability for negligence, must be conspicuous and prominently placed, and must demonstrate voluntary participation.

Most parasailing operations occur on navigable waters where federal maritime law applies. Unlike some state laws that restrict recreational activity waivers, maritime law generally permits them when properly drafted.

The gross negligence exception

Maritime public policy draws a firm line: waivers cannot cover reckless or grossly negligent conduct. This limitation applies regardless of waiver language.

Operating in dangerous weather despite warnings, using equipment known to be degraded, or ignoring established safety standards may constitute gross negligence. When operator conduct crosses this threshold, waiver protections evaporate.

Additionally, waivers that attempt to release operators from violations of federal maritime safety statutes or USCG compliance requirements are generally unenforceable. If an operator violated specific safety regulations, a waiver likely provides no protection.

Why signing a waiver doesn’t end your case

Waiver enforceability depends on specific facts: what the waiver said, how conspicuous it was, what the operator did wrong, and whether that conduct rose to the level of gross negligence or regulatory violation.

Many parasailing accident victims assume they have no options because they signed paperwork. An experienced maritime attorney can evaluate whether the waiver applies to the specific circumstances of the accident.

Frequently Asked Questions

How common are parasailing accidents?

Florida reported 6 fatalities and 18 injuries from 19 total parasailing accidents between 2001 and 2012. Nationally, the Water Sports Industry Association reports that there have been 68 parasailing‑related injuries and 10 deaths over the past ten years. While statistically rare relative to total participants, incidents tend to be severe when they occur, with drowning as the primary cause of death due to canopy and harness entanglement underwater.

What is the most dangerous part of parasailing equipment?

The towline is the single most critical failure point. Cyclic degradation from salt exposure, UV damage, and repeated winching causes towlines to weaken over time. NTSB testing found that bowline knots reduce rope strength by more than 20% and create stress concentration points where failure occurs. Many operators use lines well past their safe service life because replacements are expensive.

At what wind speed should parasailing operations stop?

Industry standards set by ASTM F3099 establish a maximum sustained wind speed of 20 mph with a gust cap of 25 mph. Florida’s White-Miskell Act codifies similar requirements into state law. The critical risk threshold is a gust differential greater than 15 mph between sustained wind and gusts, even if sustained winds remain below 20 mph.

Does signing a waiver mean I can’t sue after a parasailing accident?

Not necessarily. Maritime law prohibits waivers from covering reckless or grossly negligent conduct. If an operator launched in dangerous weather, failed to maintain equipment properly, or violated safety regulations like Florida’s White-Miskell Act, a waiver may not protect them. Each case depends on the specific facts and the nature of the operator’s conduct.

Who is liable when equipment fails during a parasailing accident?

Vessel owners and operators can both face liability under general maritime law. Owners are responsible for equipment maintenance and ensuring vessels are in safe condition. Operators are personally liable for their own negligent acts. Tour companies may face claims for negligent entrustment, failure to inspect equipment, or failure to warn of known hazards. Multiple parties may share responsibility.

Conclusion

Parasailing accidents result from identifiable, often preventable causes. Equipment failure—particularly towline failure—accounts for most severe injuries and deaths. Operator errors in weather judgment, maintenance, and emergency response create conditions for those failures. Environmental factors, especially high winds and dangerous gust differentials, amplify every other risk.

Real incidents from Panama City Beach to Ocean Isle Beach demonstrate these patterns repeatedly. When operators ignore weather warnings, extend equipment past its safe service life, or prioritize revenue over participant safety, they may bear legal responsibility for resulting injuries.

If you or a family member suffered injuries in a parasailing accident, understanding what caused the accident is the first step toward understanding your legal options. Contact Prosper Injury Attorneys to discuss your parasailing accident case.