When a child suffers harm during labor or delivery, families face difficult questions about what went wrong and whether medical negligence played a role. Medical malpractice during childbirth occurs when healthcare providers fail to meet accepted standards of obstetric care, and that failure causes injury to a mother or newborn. These cases involve some of the most serious injuries in medical malpractice law, often resulting in lifelong disabilities that require extensive medical care and support.

Florida law provides a framework for families to seek compensation when preventable birth injuries occur. Understanding how these claims work requires knowledge of both the medical context surrounding childbirth injuries and the legal standards that govern malpractice litigation in Florida.

What Is Medical Malpractice During Childbirth?

Defining the Standard of Care in Obstetric Medicine

Florida law defines the standard of care as “that level of care, skill, and treatment which, in light of all relevant surrounding circumstances, is recognized as acceptable and appropriate by reasonably prudent similar health care providers.” Under Fla. Stat. § 766.102, this standard applies to obstetricians, nurses, midwives, and other providers involved in labor and delivery.

For obstetric specialists, Florida holds them to a specialist standard when practicing within their specialty. The state has largely moved away from the traditional locality rule in favor of a national professional standard for clinical care. This means an obstetrician in Miami is held to the same clinical standards as one in Jacksonville or anywhere else in the country.

How Childbirth Errors Differ From Expected Complications

Not every adverse outcome during childbirth constitutes malpractice. Childbirth carries inherent risks, and some complications occur despite appropriate medical care. The distinction lies in whether the provider’s actions met the prevailing professional standard.

Under Fla. Stat. § 766.102(3)(b), a medical injury alone does not create an inference of negligence. If a complication was a known risk of a properly performed procedure and the patient was informed of that risk, the provider may not be liable. However, when a provider fails to recognize warning signs, delays necessary intervention, or performs a procedure incorrectly, the analysis changes.

When Medical Decisions Become Negligence

Medical decisions cross into negligence when they fall below what reasonably prudent similar providers would recognize as acceptable. In childbirth cases, this often involves failures in judgment during critical moments when timely intervention could prevent injury.

Florida courts have established that the claimant bears the burden of proving by the greater weight of evidence that the provider’s actions represented a breach of the prevailing professional standard. As articulated in Wale v. Barnes, 278 So. 2d 601 (Fla. 1973), a plaintiff must establish the standard of care, breach of that standard, and proximate causation of damages.

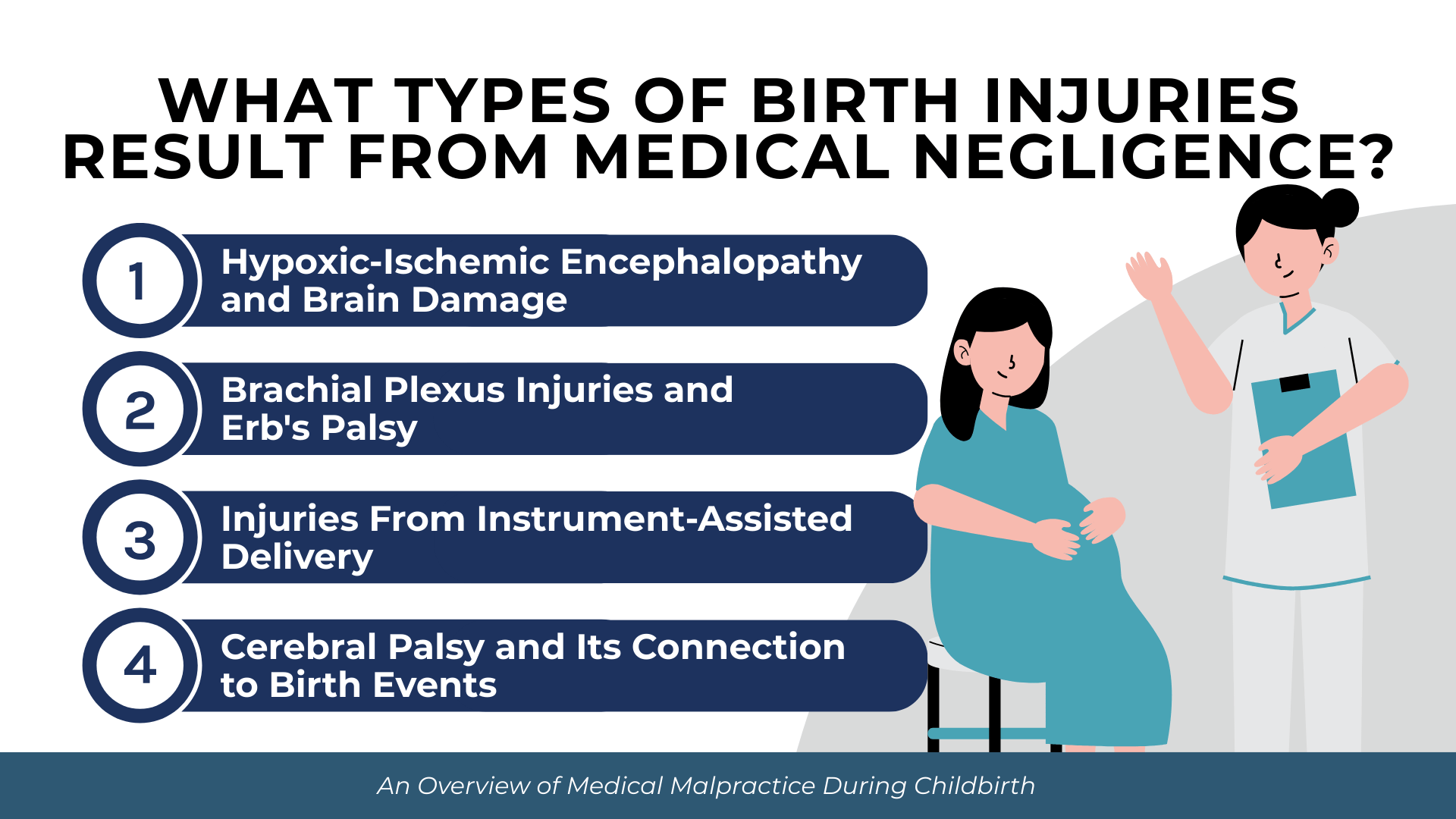

What Types of Birth Injuries Result From Medical Negligence?

Call us today at (305) 694-2676 or

contact us online for a free case evaluation.

Hablamos español.

Birth injuries resulting from medical negligence range from temporary conditions to permanent, life-altering disabilities. The severity often depends on how quickly providers recognize and respond to complications during labor and delivery.

Common birth injuries associated with medical negligence include:

- Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) from oxygen deprivation during delivery

- Brachial plexus injuries affecting the arm and shoulder nerves

- Cerebral palsy linked to intrapartum events

- Skull fractures and intracranial hemorrhage from instrument-assisted delivery

- Kernicterus from untreated severe jaundice

- Spinal cord injuries from improper delivery techniques

- Facial nerve damage from forceps pressure

Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy and Brain Damage

Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy occurs when the brain is deprived of adequate oxygen during labor and delivery. According to Medscape’s clinical reference on HIE (2024), HIE occurs in 1-3 cases per 1,000 live births in the United States and other developed countries.

The consequences of HIE are severe. According to NIH research on HIE pathophysiology (2011), 40-60% of infants affected by hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy die by age two or develop severe disabilities including cerebral palsy, epilepsy, and cognitive impairment.

Timing is critical in HIE cases. Therapeutic hypothermia (cooling treatment) can reduce brain damage if administered within six hours of birth. According to the Cochrane systematic review on therapeutic hypothermia (2013), cooling treatment reduces death or major neurodevelopmental disability by 25%, with a number needed to treat of just 7 patients to prevent one adverse outcome. Failure to recognize the need for cooling treatment or delays in initiating therapy can form the basis of malpractice claims.

Brachial Plexus Injuries and Erb’s Palsy

Brachial plexus injuries occur when the network of nerves controlling the arm is stretched or torn during delivery. According to the Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics epidemiology study (2024), brachial plexus birth injuries occur at a rate of 0.9 to 1.1 per 1,000 live births in the United States.

These injuries often occur during shoulder dystocia, when the baby’s shoulder becomes lodged behind the mother’s pubic bone. Excessive traction or improper maneuvers to free the shoulder can damage the delicate nerve bundle.

Not all brachial plexus injuries resolve on their own. According to the Canadian Paediatric Society position statement (2021), 20-30% of infants with brachial plexus birth injuries do not fully recover, with nearly 80% of those with severe global injuries experiencing persistent deficits at 18 months.

Injuries From Instrument-Assisted Delivery

The use of forceps and vacuum extractors during delivery carries significantly elevated injury risks. According to the BMJ Open study on maternal and neonatal trauma (2018), birth trauma occurs at a rate of 25.48 per 1,000 forceps deliveries compared to just 4.74 per 1,000 spontaneous vaginal deliveries—a five-fold increase in risk.

Vacuum-assisted delivery also carries elevated risk. The same study found vacuum delivery results in 14.22 birth trauma cases per 1,000 births, approximately three times the rate of spontaneous vaginal delivery. These instruments, when used improperly or in inappropriate clinical situations, can cause skull fractures, intracranial bleeding, and nerve damage.

Cerebral Palsy and Its Connection to Birth Events

Cerebral palsy affects motor function and muscle coordination, often requiring lifelong support and care. According to CDC data on cerebral palsy (2022), approximately 1 in 345 children in the United States have been identified with cerebral palsy.

An important consideration in birth injury litigation involves the cause of cerebral palsy. According to CDC guidance on cerebral palsy risk factors (2025) and systematic review evidence published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology (2008), 85-90% of cerebral palsy cases are congenital, with only approximately 14.5% associated with intrapartum asphyxia. This statistic is significant for establishing causation in birth injury cases, as it demonstrates that the majority of CP cases are not caused by events during labor and delivery.

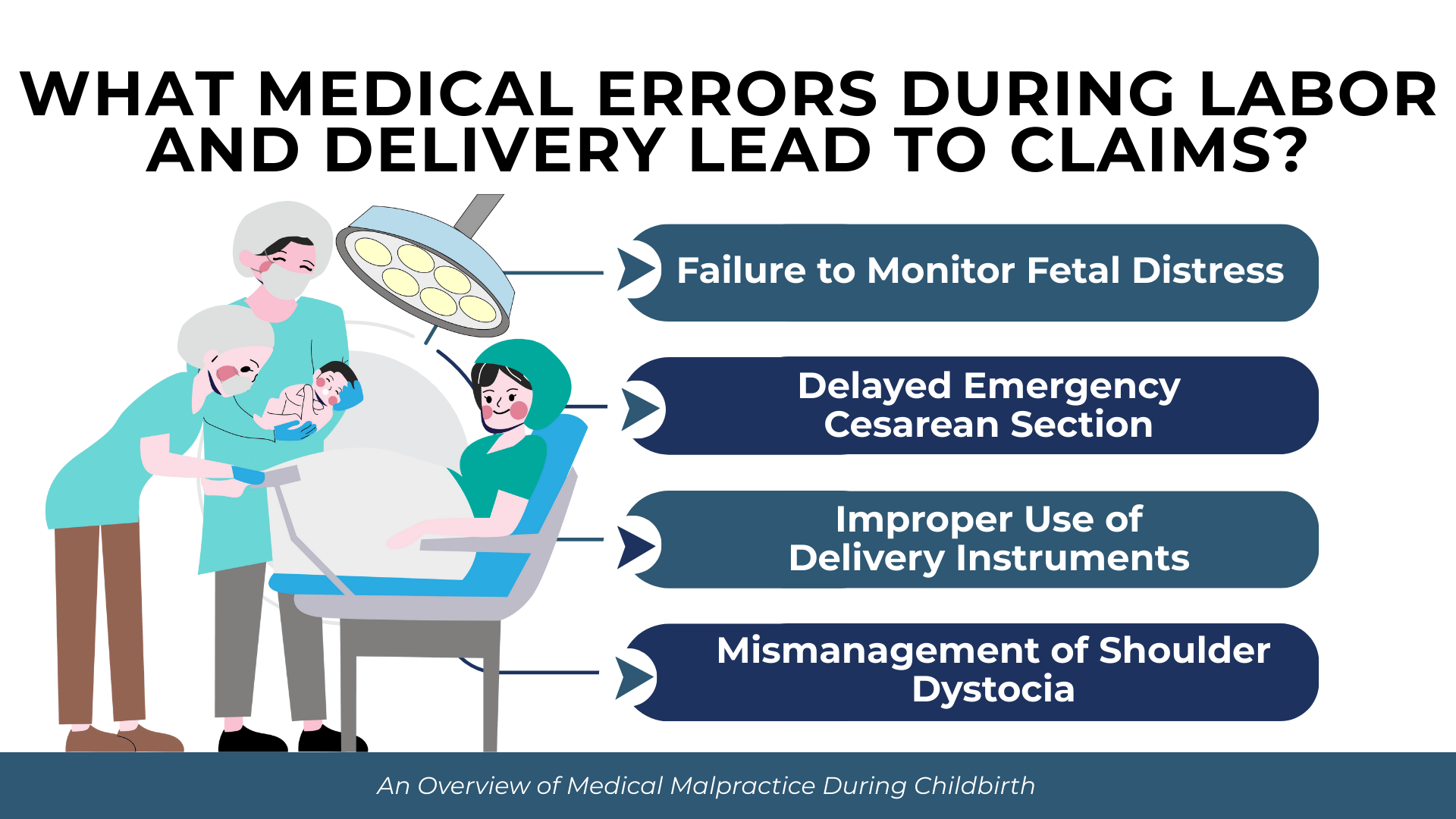

What Medical Errors During Labor and Delivery Lead to Claims?

Medical errors during childbirth typically involve failures in monitoring, decision-making, or technical performance. These errors often occur during time-sensitive situations where delays or incorrect responses can result in permanent injury.

Common medical errors giving rise to birth injury claims include:

- Failure to properly interpret fetal heart rate monitoring strips

- Delayed response to signs of fetal distress

- Failure to perform a timely cesarean section when indicated

- Improper use of Pitocin causing excessive uterine contractions

- Incorrect technique during forceps or vacuum-assisted delivery

- Failure to recognize and properly manage shoulder dystocia

- Inadequate monitoring of maternal and fetal conditions during labor

- Failure to diagnose and treat infections during pregnancy or labor

Failure to Monitor Fetal Distress

Continuous fetal heart rate monitoring allows providers to identify signs of oxygen deprivation before brain damage occurs. Non-reassuring fetal heart rate patterns require prompt evaluation and, in many cases, immediate delivery.

When providers fail to recognize warning signs on monitoring strips or delay responding to abnormal patterns, preventable brain injuries can occur. The standard of care requires trained personnel to continuously observe monitoring output and escalate concerns promptly.

Delayed Emergency Cesarean Section

When fetal distress indicates the baby is not tolerating labor, emergency cesarean delivery may be necessary. The standard of care in many situations requires the ability to begin a cesarean section within 30 minutes of the decision to operate.

Florida’s cesarean delivery rate provides context for these decisions. According to Florida Department of Health vital statistics (2023), 36.2% of all Florida births were cesarean deliveries, exceeding both national averages and WHO recommendations. While high cesarean rates raise separate concerns, delays in performing necessary cesarean sections when vaginal delivery poses risks can result in preventable injuries.

Improper Use of Delivery Instruments

Forceps and vacuum extractors require proper technique and appropriate patient selection. Applying excessive force, using instruments when contraindicated, or persisting with instrument delivery despite lack of progress can cause serious injury.

The elevated trauma rates associated with instrument-assisted delivery underscore the importance of proper training and judgment. Providers must weigh the risks and benefits of instrument use against alternatives including cesarean delivery.

Mismanagement of Shoulder Dystocia

Shoulder dystocia is an obstetric emergency that occurs when the baby’s shoulder becomes impacted behind the mother’s pubic bone after the head has delivered. According to the American Academy of Family Physicians clinical guideline (2004), shoulder dystocia occurs in 0.6-1.4% of normal-weight births but increases to 5-9% in macrosomic infants.

When shoulder dystocia occurs, providers must use specific maneuvers to safely deliver the baby. The AAFP guideline notes that brachial plexus injuries occur in 4-15% of shoulder dystocia cases. Applying excessive downward traction on the baby’s head rather than performing appropriate maneuvers can stretch or tear the brachial plexus nerves.

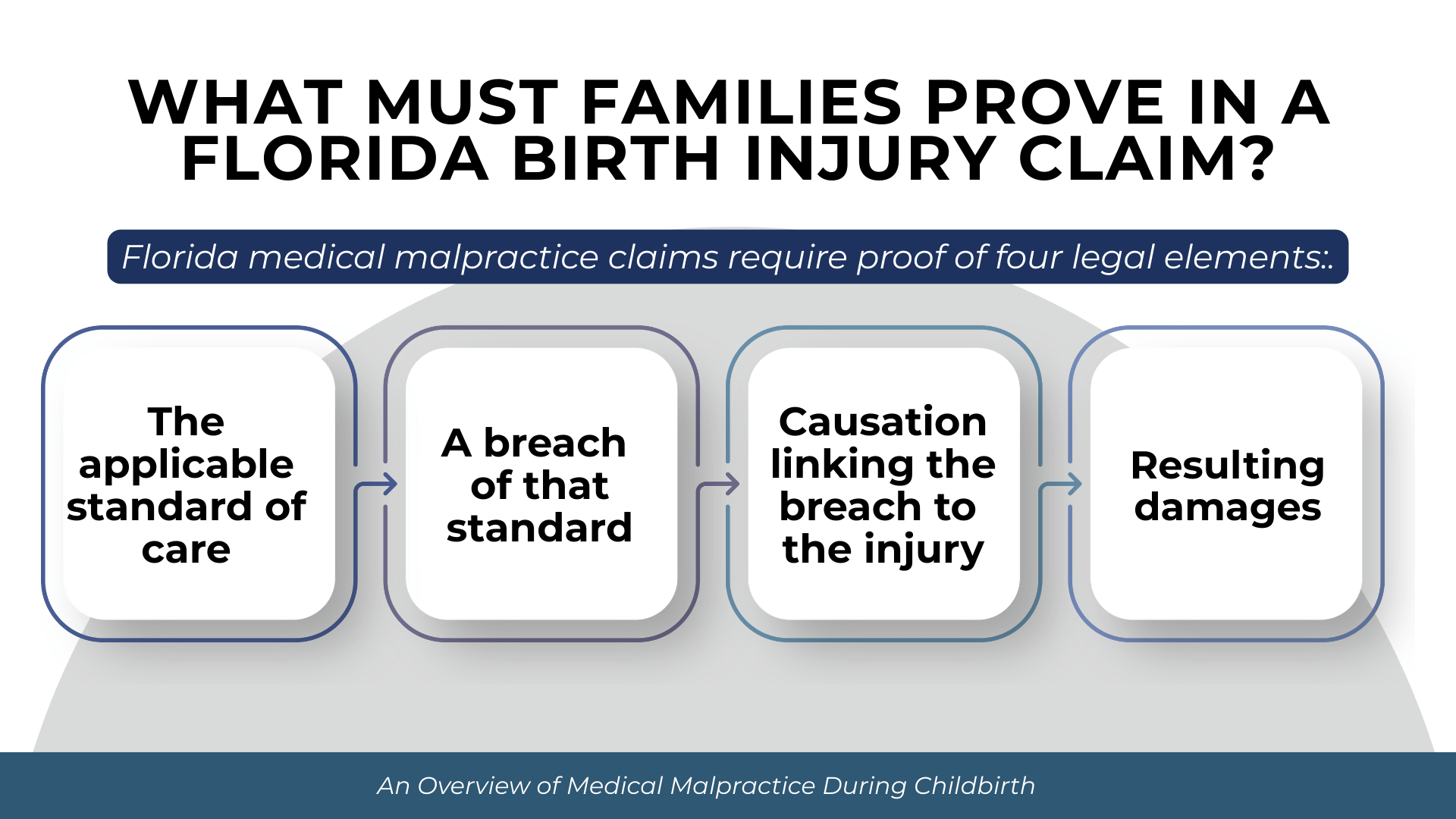

What Must Families Prove in a Florida Birth Injury Claim?

Florida medical malpractice claims require proof of four legal elements. The claimant must establish each element by the greater weight of the evidence, meaning it is more likely than not that each element is satisfied.

The four elements families must prove are:

- The applicable standard of care that governed the provider’s conduct

- A breach of that standard through the provider’s actions or omissions

- Causation establishing the breach was a substantial factor in causing the injury

- Damages resulting from the negligent conduct

Establishing the Applicable Standard of Care

The standard of care must be established through qualified expert testimony. Under Fla. Stat. § 766.102(5)(a), when the defendant is a specialist, the expert must specialize in the same specialty and have devoted professional time during the three years immediately preceding the incident to active clinical practice, instruction, or research in that same specialty.

For birth injury cases involving obstetricians, this means the expert witness must be a practicing obstetrician or have recent active involvement in obstetric medicine. The expert must conduct a complete review of pertinent medical records before offering opinions.

Proving Breach Through Expert Testimony

Expert testimony is also required to establish that the provider’s conduct fell below the standard of care. The expert must identify specific deviations from what reasonably prudent similar providers would recognize as acceptable.

In some limited circumstances, the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur may apply. Under Marrero v. Goldsmith, 486 So. 2d 530 (Fla. 1986), res ipsa loquitur instruction is appropriate where the patient was unconscious, the injury occurred to a body part remote from the surgical site, and expert testimony supports an inference of negligence. Additionally, under Fla. Stat. § 766.102(3)(b), discovery of a retained foreign body such as a surgical sponge creates prima facie evidence of negligence.

Meeting Florida’s Causation Standard

Florida requires proof that the provider’s negligence was the proximate cause of injury under the “more likely than not” standard. This means the plaintiff must establish greater than 50% probability that the injury resulted from the negligence.

Significantly, Florida has rejected the loss of chance doctrine. In Gooding v. University Hospital Building, Inc., 445 So. 2d 1015 (Fla. 1984), the Florida Supreme Court held that a plaintiff cannot recover for decreased chance of survival; the plaintiff must show the injury more likely than not resulted from the defendant’s negligence.

For birth injury cases, this means families must prove that proper medical care would more likely than not have prevented the injury. In HIE cases, for example, experts must establish that earlier intervention would more likely than not have prevented or reduced the brain damage.

Under Ruiz v. Tenet Hialeah Healthsystem, Inc., 260 So. 3d 977 (Fla. 2018), the defendant’s negligence need not be the primary cause—only a substantial factor in bringing about the harm.

Documenting Damages and Long-Term Care Needs

Birth injury cases often involve catastrophic damages requiring documentation of both current and future needs. Economic damages may include past and future medical expenses, lost earning capacity, and the cost of adaptive equipment and home modifications.

Life care planning experts are often essential in birth injury cases to project lifetime care costs. Children with conditions like cerebral palsy or severe HIE may require decades of specialized medical care, therapy, educational support, and personal assistance.

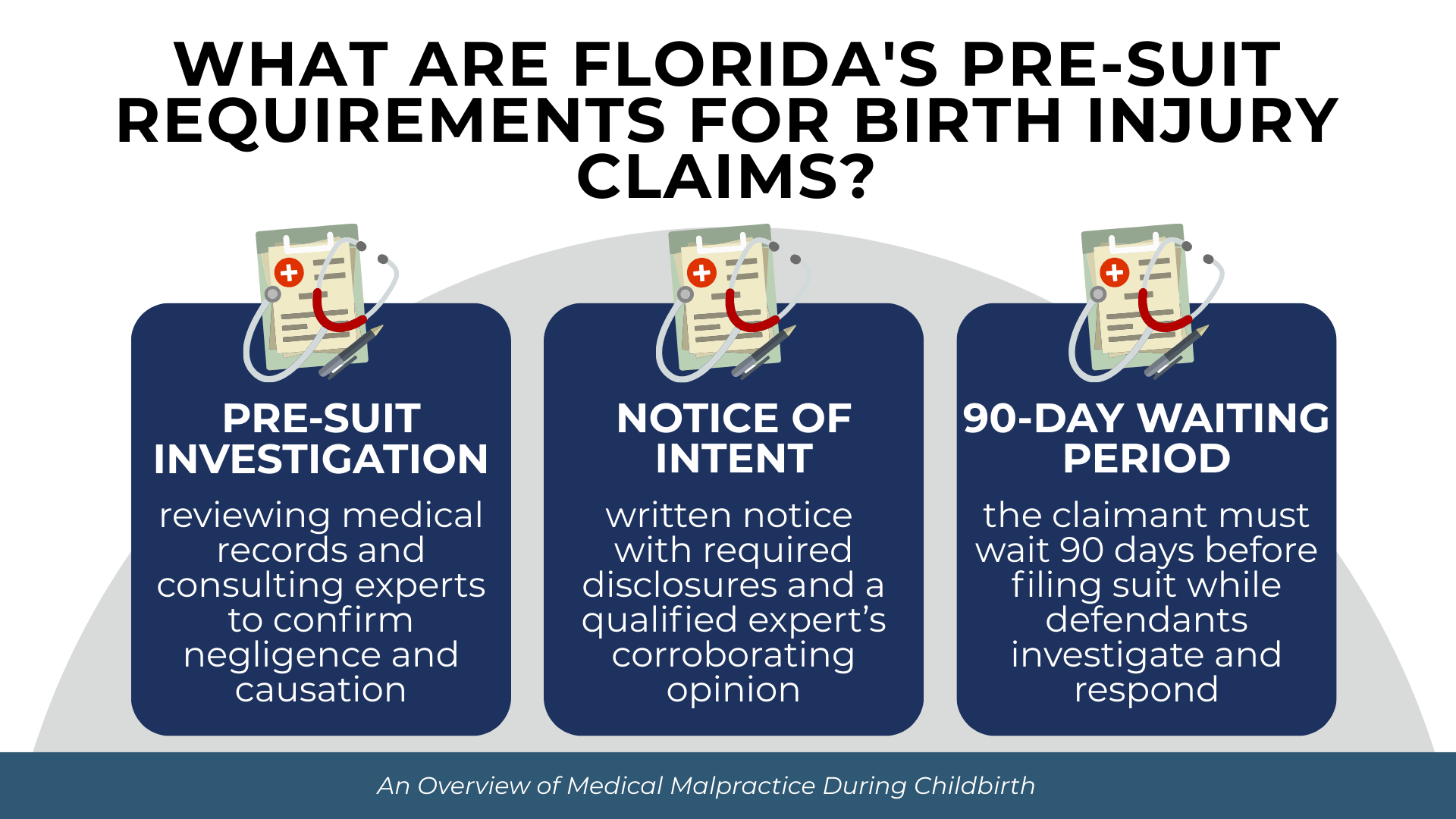

What Are Florida’s Pre-Suit Requirements for Birth Injury Claims?

Get started with your complimentary case evaluation today;

call us at (305) 694-2676 or reach us online using our

secure contact form.

Florida imposes mandatory pre-suit requirements before a medical malpractice complaint can be filed. These requirements are designed to encourage early resolution and ensure claims have merit before litigation begins.

The Mandatory Pre-Suit Investigation

Under Fla. Stat. § 766.203, the claimant must complete a presuit investigation to ascertain reasonable grounds to believe the defendant was negligent and that such negligence resulted in injury. This investigation must be completed before mailing the notice of intent to initiate litigation.

The investigation typically involves obtaining and reviewing all relevant medical records, consulting with medical experts, and analyzing whether the standard of care was breached and whether that breach caused the injury.

Notice of Intent and Expert Affidavit

Before filing suit, the claimant must serve a written notice of intent upon each prospective defendant at least 90 days before filing. Under Fla. Stat. § 766.106(2), the notice must include a list of all known healthcare providers who treated the patient for injuries subsequent to the alleged negligence, all known providers during two years before the alleged act, copies of medical records relied upon by the expert, and an executed HIPAA authorization.

Critically, the notice must be accompanied by a verified written medical expert opinion corroborating reasonable grounds to support the claim. Under Fla. Stat. § 766.203, this expert opinion must be obtained from a qualified expert who meets the specialty-matching requirements of Fla. Stat. § 766.102.

The 90-Day Waiting Period

After serving the notice of intent, the claimant must wait 90 days before filing suit. During this period, defendants must investigate the claim and respond with either a rejection, a settlement offer, or an offer to arbitrate.

The 90-day period tolls the statute of limitations. Under Hankey v. Yarian, 755 So. 2d 93 (Fla. 2000), the mandatory presuit period suspends the statute of limitations, ensuring claimants have the full benefit of their original statutory time period plus the 90-day pause.

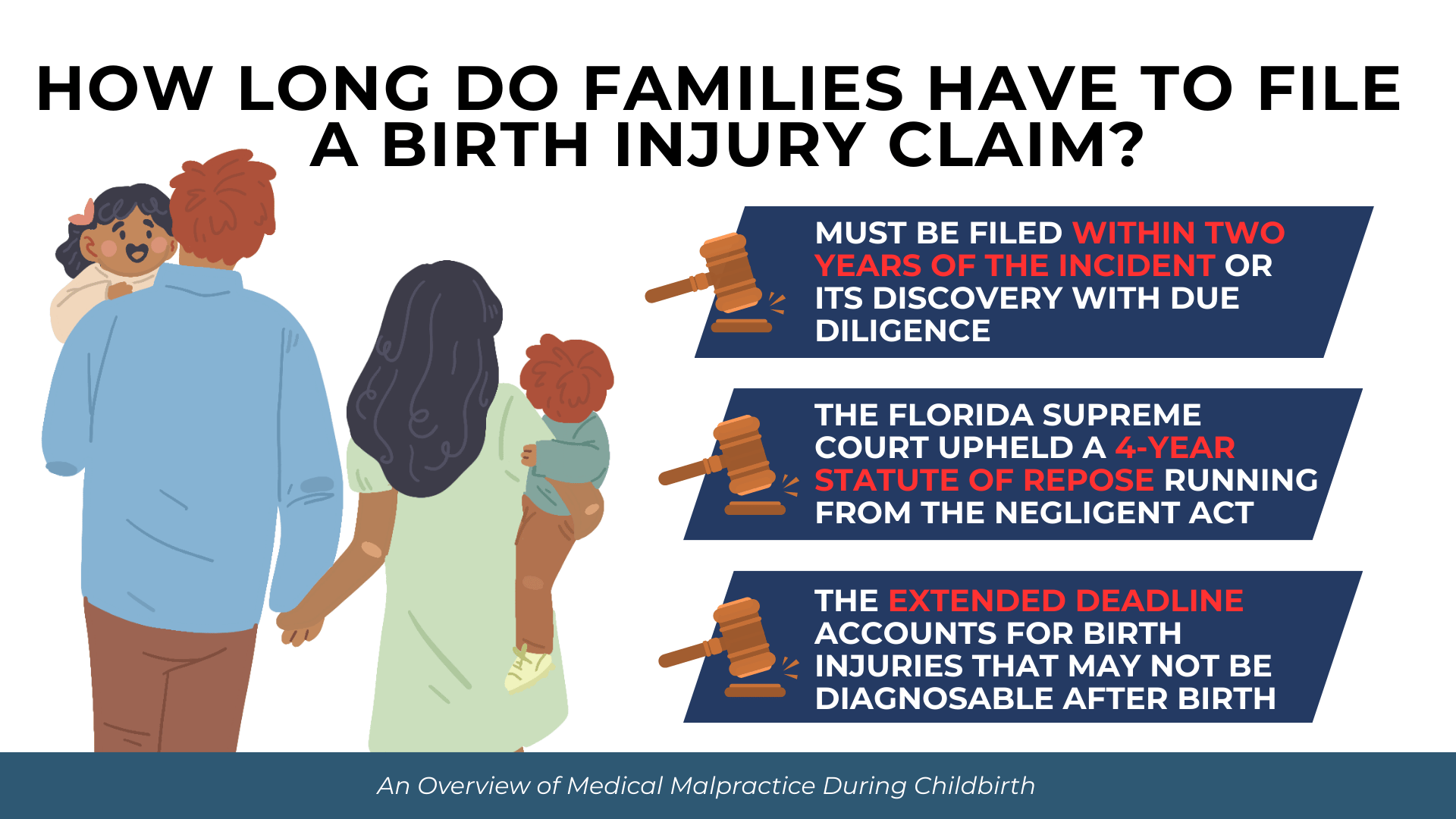

How Long Do Families Have to File a Birth Injury Claim?

Florida imposes strict time limits on medical malpractice claims. Missing these deadlines can permanently bar recovery regardless of the merits of the case.

Florida’s Two-Year Statute of Limitations

Under Fla. Stat. § 95.11(5)(c), an action for medical malpractice must be commenced within two years from the time the incident occurred or within two years from the time the incident is discovered or should have been discovered with due diligence.

Under Tanner v. Hartog, 618 So. 2d 177 (Fla. 1993), knowledge triggering the statute of limitations means knowledge of the injury and a “reasonable possibility that the injury was caused by medical malpractice.” For birth injuries, this often means the clock begins when parents learn both that their child has a specific condition and that medical negligence may have contributed to it.

The Four-Year Statute of Repose

Regardless of when an injury is discovered, Fla. Stat. § 95.11(5)(c) provides that in no event shall the action be commenced later than four years from the date of the incident. This statute of repose creates an absolute outer limit.

In Kush v. Lloyd, 616 So. 2d 415 (Fla. 1992), the Florida Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the four-year statute of repose, which begins from the date of the negligent act rather than when the injury manifests.

Extended Deadlines for Minor Children

For birth injury cases, an important exception applies. The four-year statute of repose does not bar an action on behalf of a minor filed on or before the child’s eighth birthday. This means families have until the child turns eight years old to file birth injury claims, regardless of when discovery occurred.

This extended deadline recognizes that birth injuries may not be fully apparent in the immediate aftermath of delivery. Conditions like cerebral palsy may take months or years to diagnose definitively.

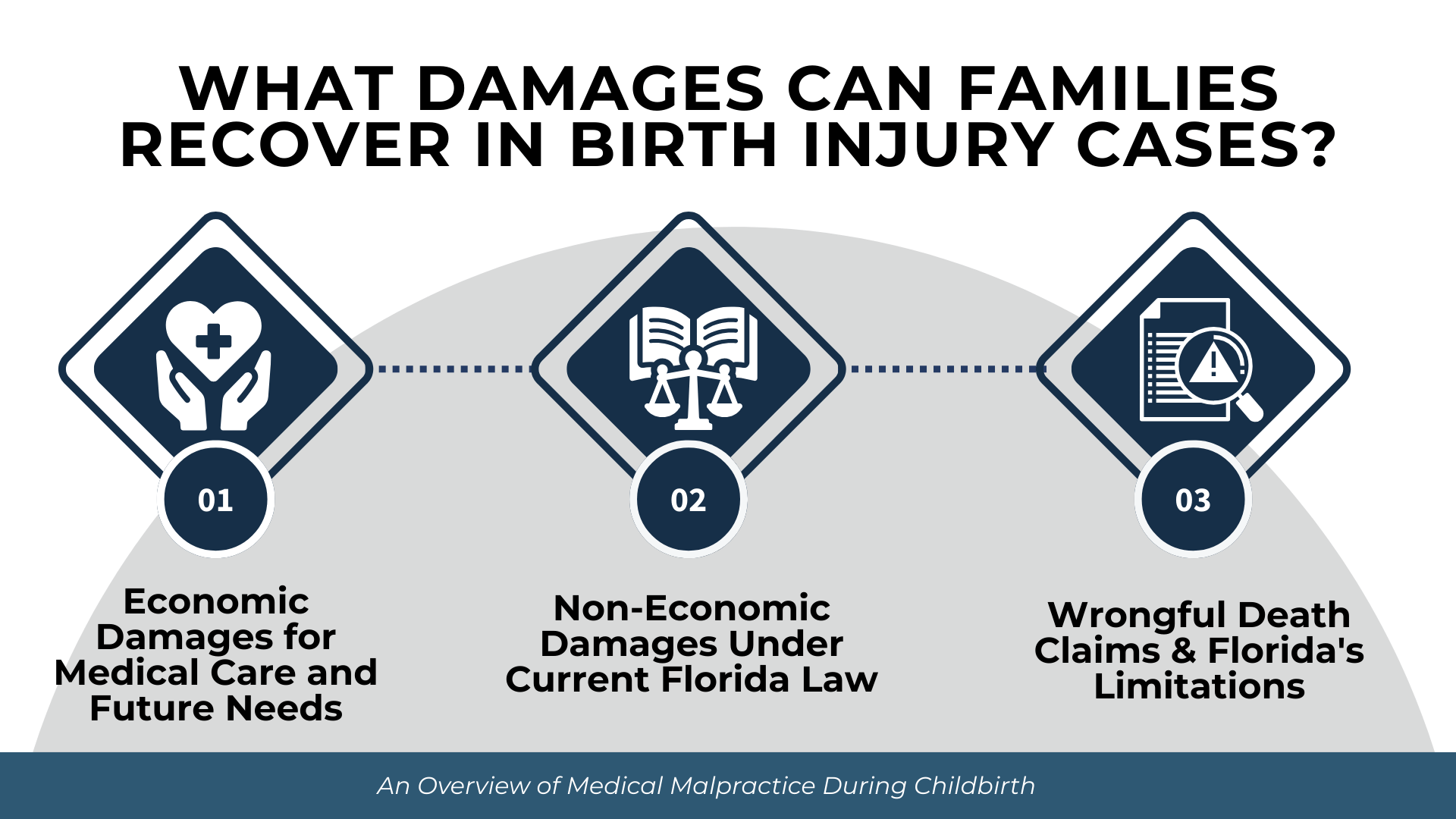

What Damages Can Families Recover in Birth Injury Cases?

Birth injury cases often involve substantial damages reflecting both the immediate harm and the lifetime of care many injured children will require.

Economic Damages for Medical Care and Future Needs

Economic damages compensate for quantifiable financial losses. In birth injury cases, these damages often include:

- Past and future medical expenses including hospitalizations, surgeries, and specialist care

- Rehabilitation costs including physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy

- Adaptive equipment such as wheelchairs, communication devices, and modified vehicles

- Home modifications to accommodate disabilities

- Special education and support services

- Lost earning capacity reflecting the child’s diminished ability to work as an adult

- Cost of personal care attendants or nursing care

Life care planning experts typically project these costs over the child’s expected lifetime. For severe injuries, economic damages alone may reach millions of dollars.

Non-Economic Damages Under Current Florida Law

Non-economic damages compensate for pain and suffering, mental anguish, loss of enjoyment of life, and similar intangible harms. Following Estate of McCall v. United States, 134 So. 3d 894 (Fla. 2014) and North Broward Hospital District v. Kalitan, 219 So. 3d 49 (Fla. 2017), statutory caps on non-economic damages in medical malpractice cases are currently unenforceable as unconstitutional under Florida’s Equal Protection Clause.

The statutory caps in Fla. Stat. § 766.118 remain on the books but are not applied. This means families pursuing birth injury claims are not subject to artificial limits on non-economic damages.

Florida courts permit per diem arguments for calculating non-economic damages, allowing attorneys to suggest a daily rate multiplied by the expected duration of suffering.

Wrongful Death Claims and Florida’s Limitations

When a birth injury results in death, Florida’s Wrongful Death Act governs recovery. The action must be brought by the personal representative of the decedent’s estate for the benefit of survivors.

An important limitation applies to medical malpractice wrongful death cases. Under Fla. Stat. § 768.21(8), in medical malpractice cases, adult children over 25 cannot recover non-economic damages, and parents of adult children cannot recover mental pain and suffering damages. This provision, known as the “Free Kill Law,” significantly limits damages when an unmarried adult without minor children dies from medical malpractice.

For birth injury deaths, this limitation typically does not apply because the decedent is a minor. The child’s parents can recover mental pain and suffering, lost support and services, and medical and funeral expenses.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I know if my child’s birth injury was caused by malpractice?

Determining whether a birth injury resulted from malpractice requires expert medical analysis. A qualified medical expert must review the medical records, identify whether the standard of care was breached, and assess whether that breach caused the injury. Because many birth complications occur despite appropriate care, expert evaluation is essential to distinguish preventable injuries from unavoidable outcomes.

Can I file a claim if my child was injured during a C-section?

Yes. Cesarean delivery is a surgical procedure subject to the same malpractice standards as any other medical intervention. Claims may arise from delayed C-section when vaginal delivery became unsafe, surgical errors during the procedure, improper anesthesia administration, or failure to properly monitor mother and baby during and after surgery. The analysis focuses on whether the providers met the applicable standard of care.

What if the hospital says the injury was an unavoidable complication?

Hospitals and their insurers often characterize injuries as unavoidable complications. However, under Florida law, the question is whether the provider’s conduct met the prevailing professional standard. An independent medical expert can evaluate whether the injury truly resulted from an inherent risk of the procedure or whether provider negligence contributed. The presence of a known complication does not automatically preclude a malpractice claim if the complication was caused or worsened by substandard care.

Does Florida have damage caps for birth injury cases?

Currently, no. Following the Florida Supreme Court decisions in McCall (2014) and Kalitan (2017), statutory caps on non-economic damages in medical malpractice cases are unenforceable as unconstitutional. Families pursuing birth injury claims are not subject to artificial limits on pain and suffering damages. However, families should monitor legislative developments as damage caps may be reconsidered.

What is NICA and does it affect my birth injury claim?

The Florida Birth-Related Neurological Injury Compensation Association (NICA) is a no-fault compensation program for certain severe birth injuries. If an injury qualifies under NICA, the program may provide the exclusive remedy, limiting the family’s ability to pursue a traditional malpractice lawsuit. NICA coverage depends on specific criteria including the type and severity of injury. Families should consult with an attorney to determine whether NICA applies to their situation and how it affects their legal options.

Conclusion

Medical malpractice during childbirth can result in injuries that affect a child and family for life. Florida law provides families with the ability to seek compensation when healthcare providers fail to meet accepted standards of obstetric care and that failure causes harm. Understanding the types of birth injuries that may result from negligence, the legal elements required to prove a claim, and the procedural requirements under Florida law helps families make informed decisions about pursuing accountability.

The statute of limitations creates urgency in these cases. Families who believe their child suffered a preventable birth injury should not delay in seeking legal guidance. Evidence preservation, timely expert evaluation, and compliance with pre-suit requirements are essential to protecting the family’s rights.

If you have questions about a potential birth injury claim, contact Prosper Injury Attorneys to discuss your situation.